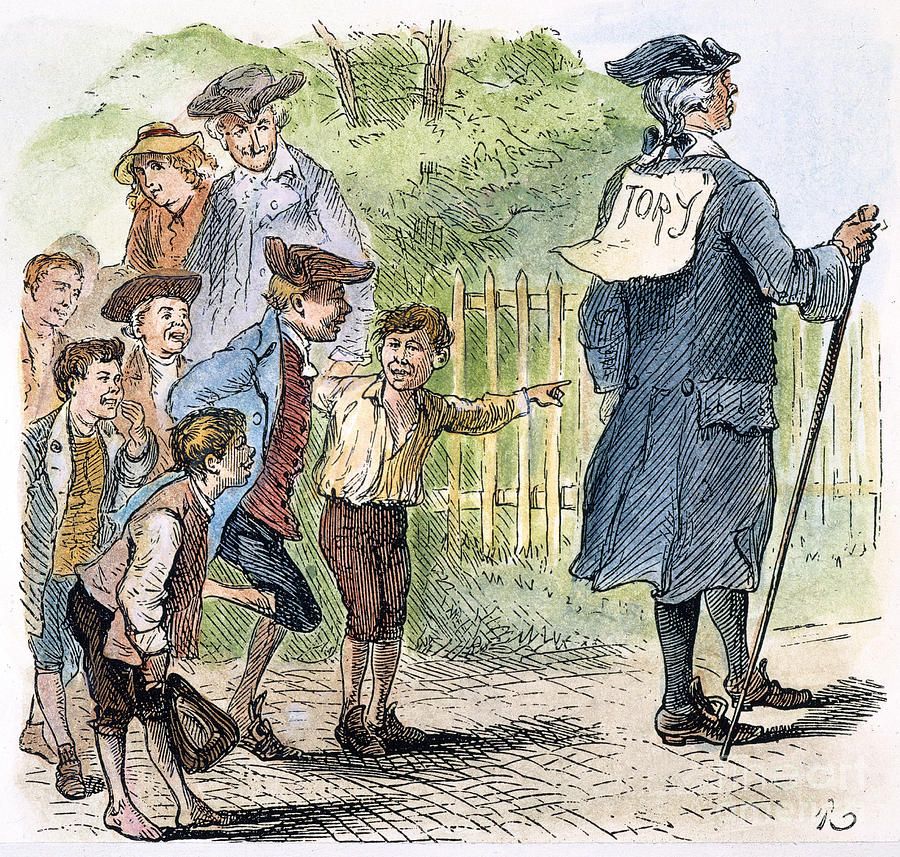

The hilarity and ridicule forced him from the courtroom. He had hoped that he would find some relief outside. His attempt to settle old scores and gain some sense of satisfaction was backfiring. Searching for fresh air, he stumbled upon an elected official who was presiding over his case bent over in laughter. Outside the courtroom, the clerk of the court was free to enjoy the joke that was at Mr. Hook’s expense. Seeking a friendly face, or at least a neutral bystander was pointless at this point. Mockery was something the proud Scotsman was unfamiliar with; his wealth and pride demanded respect. But respect from his fellow countrymen was something that he had lost years ago. John Hook was now in the final chapter of his ejection from Virginian society. Hook was an accused loyalist, whether he was or was not is up for debate. But in the eyes of his fellow Virginians, Hook had betrayed his country.

Now that the war was over, he found himself in court just like he was before the war had begun. His problems started when the war started, and now with the British surrender, Hook found himself under fire again. This time he was in the crosshairs of arguably Virginia’s most famous orator Patrick Henry. It was Henry’s legendary skill that had him chased with laughter from the courtroom. Before the war, in the spring of 1775, it was whispered that Hook had expressed his disgust with the Americans’ behavior at the destruction of the tea into Boston Harbor. By June of 1775, Hook was summoned to appear before the local magistrate to account for his words. It was said that Hook claimed there would be no peace until the “Americans get well flogged.” Comments such as these advertise the attitudes of British sympathizers during the war. The complex realities of the loyalist involvement in the war often get pushed to the side to make room for other scholarships. The number of loyalists is still a matter of historical debate, some historians believe there may have been as many as 100,000 loyalists in a population of 2.5 million. All were dealing with a wide variety of contention and outright violence. John Hook’s situation grants us a glimpse into the world of British loyalists. Through his troubles, we can perceive what other loyalists may have had to endure.

Beyond the personal experience of one loyalist, Hook’s life also shows the speed at which the country was galvanized together, disregarding distance or localities. John Hook lived in western Virginia, which was a far distant place from the center of the action, Lexington and Concord. Yet the solidarity of spirit was binding the vast colonies together. Hook was to account for his words around the same time his fellow Virginian, George Washington, was appointed to Commander of the Continental Army. Now the appointment of Washington may appear on the surface to have nothing in connection to the fate of Hook; it does reinforce the unification of the Colonies. In fact, the first letter of disapproval transcribed to Hook was dated June 16, 1775, dated just one day after Washington’s appointment. It is highly unlikely that the region would have been notified of Washington’s appointment before Hook’s summons was sent out. This weakens some historical speculation that Washington received the Continental commission to link the South to the fate of New England. Instead, the date of Hook’s letter suggests Virginia was already caught up in the rapture of patriotic fervor.

Additionally, Hook’s initial defense of his comments magnified the increasing unity between Massachusetts and Virginia. After attempting to fain ignorance of his comments, when he was presented with his own remarks, he tried to clarify his statement in a very revealing way. Hook alleged that his criticisms of “Americans” were directed or should have been interpreted as meaning “Bostonians.” This pathetic attempt failed to save his own hide, but it does illuminate the striking realities. Hook’s defense exposes his own ignorance to the changing environment around him. The men of New London may have once considered themselves a breed apart from there northern neighbors. But no longer, now they embraced Massachusetts even as the other was in a desperate situation. The yoke of British oppression and the siege of Boston Harbor had failed not only to break Boston, but it unified the colonies.

The vignette of John Hook opens a multitude of avenues for potential historical research regarding loyalists during the war. Just as the lives the of people New London were different from those of their Boston countrymen, the lives of loyalists must have also be impacted by region impacts. Vicinity to British strongholds or the later years of the war would all provide fascinating considerations to consider regarding the lives of John Hook and other loyalists.

“John Hook as a Loyalist.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 33, no. 4 (1925): 399-403. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4244041.

Brown, Wallace. “THE LOYALISTS AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.” History Today, Mar 01, 1962. 149, http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/docview/1299038652?accountid=12085.

Read, Daisy. New London: Today and Yesterday. Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell, 1950.