The coal industry was a vibrant catalyst for the development of the American economy in the mid to late eighteenth century. Coal’s versatility proved to be its secret weapon as it was able to stay viable in the rapidly transforming market of the period. This dynamic aspect of the mineral kept it as the vanguard of technological innovation that propelled a primarily agrarian nation to the apex of the highly competitive Industrial Age.

Research into the coal industry can provide a fascinating perspective into two distinct regions before and after the Civil War. These differences emphasize the expanding cultural differences that separated the North from the South, which expanded into an irreconcilableseparation. Coal offers a case study in the regional examples of Pennsylvania and Virginia, showcasing the vast differences that had developed even between two neighboring states. In the early years of the republic, coal was appreciated for its potential importance to the expanding economy. Both Alexander Hamilton and AlbertGallatinforesaw its importance, but they could have never predicted the technological advances that would magnify the importance of coal. [1] These advances would also develop and change the culture of the two regions. The most significant gulf between Pennsylvania and Virginia was the distinct economies they developed throughout the colonial period and into the 1800s. Pennsylvania had abolished slavery on paper in 1790, but it still existed within the state in a decreasing fashion. In comparison, Virginia’s robust economy saw an increasing dependence on slavery. According to historian Sean Patrick Adams, slavery was used to produce coal in the Richmond region, along the James River, but this work was considered secondary to the demand for slave labor on the region’s plantations.[2] Virginia’s inability to pull away from the plantations’ power greatly hinder the development of the coal industry compared to that of Pennsylvania.

In the decades before the war, both states exhibited a difference in supported growth. Pennsylvania glared at charters with suspicion compared to Virginia, where they were welcomed into the market. Between 1835- 1840, Virginia passed “172 mining and manufacturing charters” while attempts to pass charters in Pennsylvania initiated full-scale push back from all sides.[3] One reason for this tension was the expanding influence of the coal industry across Pennsylvania. During this period, coal in Virginia mostly centered around the Richmond area, while the rich deposits in the western mountain region were yet to be fully appreciated. Thus, the charters were never perceived as the state tilting the entire economy in coal’s favor. Unlike Virginia, coal had a unifying reach across much of Pennsylvania, possibly enabling it to enforce its will upon the state’s other industries. This statewide stranglehold that made Pennsylvania fearful of one all-powerful conglomerate reflected the power the slaveholding elite already enjoyed in Virginia.

By 1845 the expense of coal mining impacted both states. Collecting coal close to the surface became much harder, thus forcing the cost of mining to increase. As mining was forced further underground, companies were forced to reach deeper into their own pockets to keep their business afloat. Transportation of coal also became an issue with the chaos along the waterways. By the mid-1840s, the struggling industry showed minor signs of the behemoth it would soon become. Two acts of legislation passed by the Pennsylvania legislature in 1849 and 1854 helped support the industry’s growth and the development of corporations. With the risk of loss increasing, these acts supported the surrounding aspects of the industry.

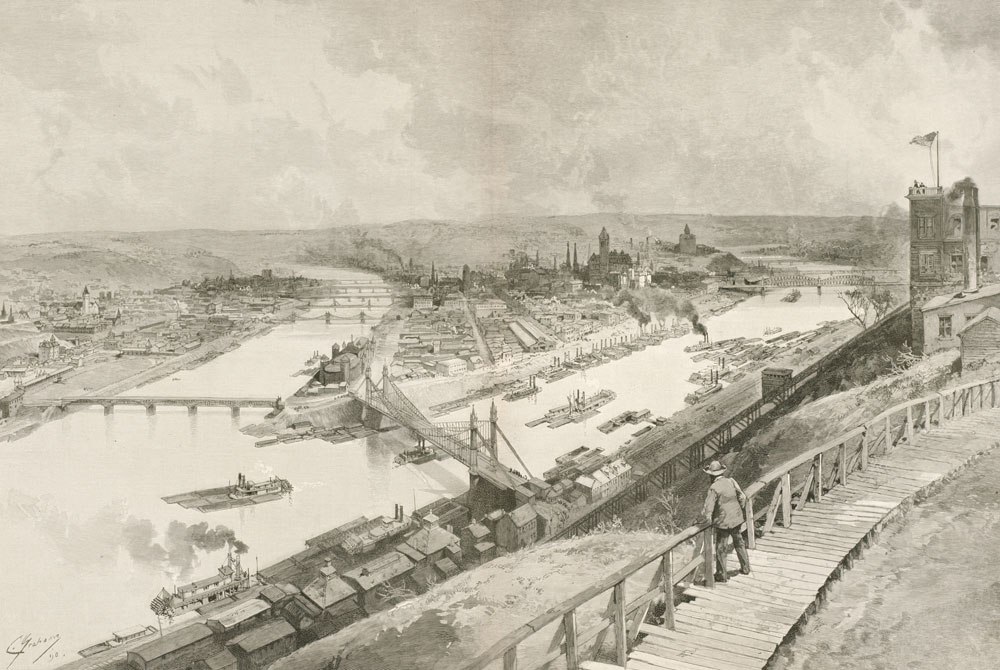

Additionally, Adams contends that unresolved issues from the 1830s between eastern and western Virginia tore at the loose threads that kept the commonwealth together.While coal created a division in the Old Dominion, it was unifying the Keystone state. In Pennsylvania, the success of the coal industry had the potential to strengthen the whole state. In contrast, western Virginia’s industrial success threatened the traditional power of the plantations, “like nearly every other political issue in antebellum Virginia, it was influenced by sectionalism.” [4] When the bitter sectionalism finally exploded into the Civil War, the need for coal was realized again. During and immediately after the war, the railroads emerged as the dominant industry that would move the unified country forward. This only intensified the need for coal as the nation moved forward and westward. Expansion exposed the friction of Virginia’s coal industry and the loss of the valuable coal region that now made up West Virginia.The Richmond region that once was seen as having so much potential was only seen as a lost opportunity.Exaggerating this disappointment was the explosion of the coal industry in southwestern Pennsylvania. Advancements in technology increased the importance of coke in the coal industry. The Monongahela Valley proved to be a vast coke reservoir, turning the region’s rivers into a highway for the coke and steel industry. The demand for steel and the geographic advantages of western Pennsylvania and the mining of West Virginia forever pulled the focus away from Virginia’s tidewater region. An 1886 issue of Harper’s Weekly describes the fleet of steamers carrying coal on the three rivers surrounding Pittsburgh. The article proclaims, “nothing like it can be seen anywhere else in the world.” [5]

The lopsided tilt of the industry in Pennsylvania’s favor over Virginia was due to more than a few factors. Slavery obstructed the development of Virginia’s coal industry, struggling to pull the labor from the plantations. Additionally, Virginia’s resistance to corporations in the 1850s was a devastating instinct. The division of the rich mountainous coal region of West Virginia in 1863 effectively ended any chance of competing with its northern neighbor. The rise of bituminous coal and the river valleys leading to Pittsburgh revealing itself to be an endless spring of coke closed the door on any real competition between the two regions.

[1] Adam, Sean Patrick. “US Coal Industry in the Nineteenth Century”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. January 23, 2003. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-us-coal-industry-in-the-nineteenth-century/

[2] Idib.

[3] Adams, Sean Patrick. “Different Charters, Different Paths: Corporations and Coal in Antebellum Pennsylvania and Virginia,” Business and Economic History 27, no. 1 (Fall, 1998): 78-90, http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F220046232%3Faccount: 80

[4] Adams, Sean Patrick “Different Charters, Different Paths: Corporations and Coal in Antebellum Pennsylvania and Virginia,” Business and Economic History 27, no. 1 (Fall, 1998): 78-90, http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.proquest.com%2Fdocview%2F220046232%3Faccount: 86

[5] “Coal Boats on the Ohio.” Harper’s Weekly, March 27, 1886. https://app-harpweek-com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/