The stock market crash of 1929 that hurled the American economy into the Great Depression still haunts modern economists and historians. The former head of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, rightfully referred to it as the Holy Grail. Its presents looms large over the imagination of Wall Street, Academia, and the halls of the Capital. It presents itself as both a menacing specter and the ultimate enigma challenging those brave enough to try. Like the stones collected on the Salisbury Plain, it holds a new fascination for each generation to ponder its reality. It is not that the attention it garners is undeserving, instead, the impact of the crash and the wake of the Depression are hard to comprehend for the modern audience. The years of anguish and pain it caused upon society demand a focused examination. Yet with all the energy it has pulled into its sphere, there is still no census for the cause or conclusion.

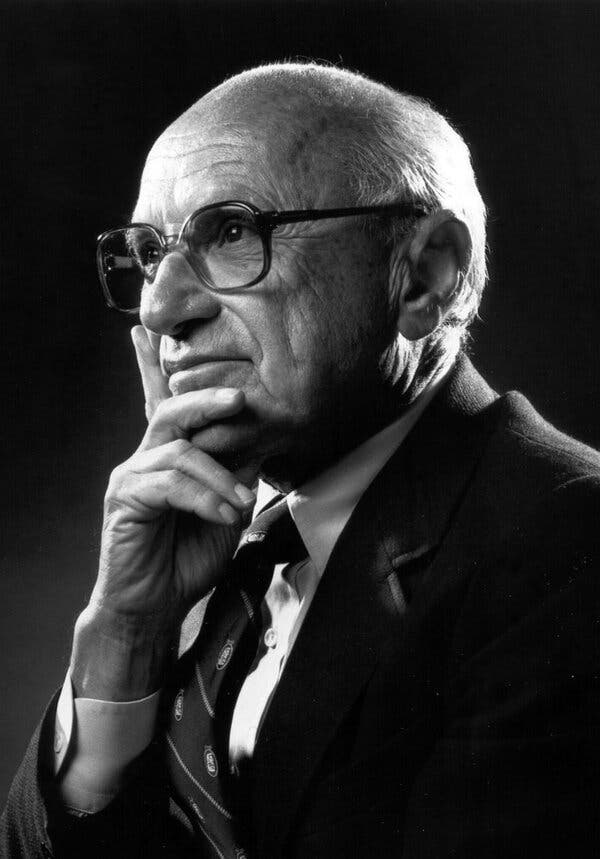

Those who have investigated the events have congregated into two unified factions, one camp holding the view that the reverberations of the market’s crash were so powerful that it cracked the foundations of the economy and sunk the world into a depression. In contrast, the others see the crash as a natural occurrence of market fluctuations. And it was the government’s intervention and meddling that made a bad situation worse. Leading the vanguard of the second group is renowned economist Milton Friedman. Friedman contends that the “Depression was produced by a failure of government, and by a failure of monetary policy.” He also directs blame at the failure of the Federal Reserve to act in its properly intended way. Eugene White agrees with Friedman contending the Federal Reserve’s protection to keep the bubble from bursting on its own “pushed- the economy further into a recession.”

Milton Friedman created a career for himself speaking plainly about complex topics. His style of cutting through the chaos generated a position for himself as a popular economist if there ever existed one. Even today, his video clips are popular among conservatives and libertarians. Part of Milton’s brilliance and popularity stemmed from his ability to cut through another’s argument with katana like speed and precision. This skill set helped him understand that much of the confusion surrounding the research of the Great Depression stemmed from strict adherence to an ideology. As Hugh Rockoff comments in his review of Friedman and Schwartz’s work, “The Great Depression, and the way it was interpreted by Keynesian economists, convinced a generation of American intellectuals that only socialism (or near-socialism) could save the American economy from periodic economic meltdowns.” Devotion to their ideology that government intervention into the economy is the only safeguard against the potential turbulence of the market demands them to see data that is not supported by the statistics.

Released from the restraints of trying to justify a political view, Friedman presents a concrete argument that it was failed monetary policy that caused the Great Depression. Compounding this was the continual intrusion of the government in unsuccessful endeavors to alleviate the disaster. Friedman is not alone in this viewpoint. Economist Thomas Sowell supports this theory by showing that “unemployment peaked at 9 percent, two months after the stock market crashed– and then began drifting generally downward over the next six months” Supporting his argument even further, in June of 1930, the government took the first of its aggressive counteractions to stabilize the economy. But six months after taking these steps, “unemployment shot up into double digits– and stayed in double digits in every month throughout the entire remainder of the decade of the 1930s.”Statistics like those presented by Sowell are hard to ignore unless you consider the devotion of the opposition, as stated earlier. This offers a genuinely fascinating dynamic when contrasting this with the Keynesian perspective, promoting the theory that government intervention pulled the American economy out of the Depression. This hypothesis has also motivated endless government intervention ever since.

Bolstering his argument even further, Sowell compares the crash of 1987 to that of 1929. Both crashes were eerily similar in the early stages, with entirely unique outcomes. But, unlike the 1929, six months after the crash of 1987, the Reagan administration ignored the demands for the government to intercede in the market. Letting the market regulate itself, the crash of 1987 did not plummet the American economy into a depression. Unfortunately, the administrations under Hoover and Roosevelt wanted to end the grueling cycle but seemed only to perpetuate the downturn.

Economic History is a challenging field that demands a strong foundation in a variety of different disciplines. When approaching something as commanding as the Great Depression, researchers must be careful not to get tossed about in its wake. The sheer toll it had upon society is hard to grasp, considering the very nature of its magnitude. Yet, something so precarious that it hurts society and the individual on a grand scale demands an extensive examination. Historians have a duty to explore the events and report what they find in hopes of not only understanding the causes but also helping to contextualize and maybe prevent another such occurrence. Yet if that inquiry is constrained by blind devotion to something other than the facts, then the research is meaningless.

Bibliography

Bernanke, Ben S. “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 27, no. 1 (1995): 1-28. Accessed June 20, 2021. doi:10.2307/2077848.

Friedman, Milton. “The Great Depression Myth” http://www.LibertyPen.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dgyQsIGLt_w

Rockoff, High. “On Monetarist Economics and the Economics of a Monetary History.” Review of Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press (for the National Bureau of Economic Research), 1963. xxiv + 860 pp.

Sowell, Thomas. “The Myth of how the Great Depression was Resolved” The Washington Examiner, June 18, 2010. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/thomas-sowell-the-myth-of-how-the-great-depression-was-resolved

White, Eugene N. “The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 2 (1990): 67-83. Accessed June 20, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942891.